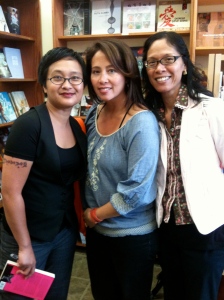

Thanks very much to Ms. Barbara Jane Reyes for inviting me to read with her and the wonderful Maiana Minahal at Eastwind Books in Berkeley last Saturday. I have long admired the talented Ms. B.J. not only for her work (if you do not yet have a copy of her new book, Diwata, what in the world are you waiting for?), but for her generosity of time and spirit when it comes to helping others promote their work; spreading the news about opportunities, resources, and new publications; connecting writers; and just being awesome, basically. Here are the three of us, post-event:

I’ve read at Eastwind Books many times now, and I continue to be grateful and astonished that 1) they still—in this age of Amazon and corporate chains—exist and 2) their support of Asian and Asian-American writers is as steadfast as ever. Does it cost more to purchase a book at Eastwind? Yes, it does. If you can, should you purchase it anyways? Yes. Yes. Please, yes.

Maiana started us off yesterday with poems from her book Legend Sandayo, which was inspired by a Filipino legend that is—according to Leny Strobel’s introduction—remembered today only in fragments. Maiana presents readers with a retelling about Sondayo, who in the original version of the story is a village woman and warrior whose husband is stolen away by the wind goddess. Sandayo battles the wind goddess for several days and finally emerges victorious, husband in tow. Sometimes it is the poet who speaks, sometimes the husband, sometimes Sandayo herself. I love the way Maiana read this poem; the rhythm was beautiful (read it out loud yourself!):

poem for sondayo

sometimes i think

i want to say

you a honeysuckle smell

on a hot day/ n

you the sculpture come from

a wet bar of clay/ n

you a new love letter

every day of the week!/ n

you a song song sondayo

i got to keep singing

can’t help but be singing

n then again

i think

you more

you a operatic orchestration

a movement in the key of “a”

a symphonic suite of arias that start

sondayo

sondayo

sondayo

you the pure pool of water

cool rain leaves

you low rumbling thunder

rolling along the sea

you strong for speakin/ n

i want to say

you living breathing dancing singing

you flame fire earth

you a song song sondayo

i got to sing

See? Gorgeous. Maiana also read from a memoir-in-progress. Though we share space in Marianne Villanueva and Virginia Cerenio’s anthology, Going Home to a Landscape, Maiana and I somehow managed to not meet while doing readings for that book, so I was extra pleased to make her acquaintance this weekend. Oh—and here’s another thing I love about Maiana’s book. Look at the size of it, here! It’s the white book in front; the ultimate in portable poetry:

I went next, and I was super surprised when I maneuvered around the podium, turned around, and saw that we had a capacity crowd. Mostly students, from the look of it, and soooo quiet. I had been trying to figure out exactly what to read and in the end, I hope I chose well. I started off by confessing that I’d had to call my Dad that morning just to make sure I was pronouncing “dugtungan” correctly. I introduced my (sadly) absent co-authors and shared this definition that one of them had found:

dugtungan: to add, expand, build on. In a cultural context this has become an event, an activity, a contest in which stories are told with successive participants adding a paragraph, a sentence, or even a specified number of words, until one by one, the writers falter and drop out.

I described the novel as a story about a modern-day Filipina-American, Tess, who finds solace in the life of one of her foremothers (Angelica) who has, until this point, maintained a mythical standing within the family. Tess has the opportunity to move beyond the myth and discover the realities of Angelica’s difficult life via letters and journal entries. I read a few pages from the beginning of the book that I felt were a good introduction to both main characters:

When Tess was a ponytailed girl in Manila sitting at the foot of Lola Josefina’s chair, she was treated to tales about budding romances between houseboys and young maids fresh from the province; about schoolchildren caught spying on the secret lives of nuns; about the hardship of life during the war. And while she listened, fascinated, to all of these stories (often while sucking absentmindedly on a li hing mui), it was the ones about Angelica she loved the most. She committed every detail to memory and believed every word. It seemed completely plausible, for example, that not just one but several of Angelica’s suitors had entered the priesthood after her firm (though never cruel) rejections.

Tess and her family left Manila for Chicago when she was nine years old so that her father, an architect, could follow a job lead that never actually materialized. After a single winter in that windiest of cities, they re-settled in California. It only took a few years before Tess, like her American counterparts, began to display a jaded personality and lost her tendency to believe in the fantastical. By the time she became a teenager, the stories about Angelica seemed like fairytales Lola Josefina had invented to ward off the boredom of sweltering, rainy-season afternoons. “She received hundreds of marriage proposals,” Lola had said, clucking her tongue. “And a botanist named a species of blood-red orchid after her when he caught sight of her walking with a market basket hanging from the crook of her elbow.”

In college, Tess’ attitude towards her foremother depended entirely on the state of her personal life at any given moment. When in love (or what she believed to be love), she thought of Angelica as an ideal romantic heroine. When distraught, she became annoyed at Angelica’s sway over the hearts and minds of everyone around her. Had some wealthy fool in Davao truly commissioned ornate buildings to honor her beauty? Was there really a hospital wing filled with women who’d gone mad with jealousy at the sight of her?

There were long stretches of time in her life—at the beginning of her marriage, for example—when she had thought very little about Angelica. But now, with Tonio’s private phone calls and weekend disappearances, Angelica was as much on her mind, and in her imagination, as she had been all those years ago in Manila. Tess often spent evenings alone while Tonio was God-knows-where, conjuring up an image of Angelica and trying to tease the facts from the maze of fiction surrounding the woman. But she could never be sure what was real, what could be depended on. In the end, Tess thought, we choose to believe what we want to believe. Especially when what we want to believe in is love.

I also wanted to share a little bit from the historical narrative, which we present almost entirely in an epistolary fashion, so I read one of Angelica’s letters that describes the beginning of her journey to Cebu in search of her lover. And that was that.

Barbara Jane wrapped up the afternoon with poems from her new book, Diwata. A diwata is a mythic creature—a nymph or fairy, perhaps, but another definition for the word is “muse,” and of course it’s the one B.J. likes best. Many of the pieces are prose poems, and they are so rich, so…I don’t know…the only word I can think of is “world-creating,” and that’s not even a word. Jewels, each and every one:

Aswang

I am the dark-hued bitch; see how wide my maw, my bloodmoon eyes,

And by daylight, see the tangles and knots of my riverine hair.

I am the bad daughter, the freedom fighter, the shaper of death masks.

I am the snake, I am the crone; I am caretaker of these ancient trees.

I am the winged tik-tik, tik-tik, tik-tik, tik-tik; I am close,

And from under the floorboards, the grunting black pig,

Cool in the dirt, mushrooms between my toes, I wait.

I am the encroaching wilderness, the bowels of these mountains.

I am the opposite of your blessed womb, I am your inverted mirror.

Guard your unborn children, burn me with your seed and salt,

Upend me, bend my body, cleave me beyond function. Blame me.

Certainly Barbara Jean and Maiana’s work was complementary, and I like to think that because Angelica, too, is shrouded in myth, this helped our book fit in nicely with the afternoon’s poetry. And now…I need to move away from the keyboard for awhile!

Thanks for reading! Check back soon!

~ Veronica

What It Is (Drawn & Quarterly, 2008) and Picture This: The Near-Sighted Monkey Book (Drawn & Quarterly, 2010) by Lynda Barry. Writers and artists will be inspired by these two unorthodox “manuals” for the creative life. Written by hand and filled with Barry’s color-saturated collages, drawings, doodles, and whatnot, they’re pretty much impossible to put down.

What It Is (Drawn & Quarterly, 2008) and Picture This: The Near-Sighted Monkey Book (Drawn & Quarterly, 2010) by Lynda Barry. Writers and artists will be inspired by these two unorthodox “manuals” for the creative life. Written by hand and filled with Barry’s color-saturated collages, drawings, doodles, and whatnot, they’re pretty much impossible to put down. Pinoy Capital: The Filipino Nation in Daly City, by Benito M. Vergara, Jr. (Temple University Press, 2009). Like thousands of Filipinos before me, and hundreds of thousands after me, I grew up in Daly City. This is a fascinating anthropological take on my hometown, written in a style that is somehow both academic and conversational. A must-have for the bookshelf of anyone with even a tangential interest in a landscape that holds special meaning for Filipinos.

Pinoy Capital: The Filipino Nation in Daly City, by Benito M. Vergara, Jr. (Temple University Press, 2009). Like thousands of Filipinos before me, and hundreds of thousands after me, I grew up in Daly City. This is a fascinating anthropological take on my hometown, written in a style that is somehow both academic and conversational. A must-have for the bookshelf of anyone with even a tangential interest in a landscape that holds special meaning for Filipinos. A History of the Philippines from Indios Bravos to Filipinos, by Luis Francia (Overlook Press, 2010). A history of the Philippines written by a poet/journalist? Who could resist such a fine book? Pick up two copies: one for yourself, and one to offer as a gift to someone who has been very, very good this year.

A History of the Philippines from Indios Bravos to Filipinos, by Luis Francia (Overlook Press, 2010). A history of the Philippines written by a poet/journalist? Who could resist such a fine book? Pick up two copies: one for yourself, and one to offer as a gift to someone who has been very, very good this year. Imago, by Joseph O. Legaspi (CavanKerry Press, 2007). I had the chance to hear Joseph read from the poems in Imago when he participated in the PAWA Reading Series earlier this year, and was instantly drawn to his work. He captures all the beauty and innocence of childhood, tempered by the inevitable intrusion(s) of death, violence, sex (the confusing parts, that is). So good.

Imago, by Joseph O. Legaspi (CavanKerry Press, 2007). I had the chance to hear Joseph read from the poems in Imago when he participated in the PAWA Reading Series earlier this year, and was instantly drawn to his work. He captures all the beauty and innocence of childhood, tempered by the inevitable intrusion(s) of death, violence, sex (the confusing parts, that is). So good. Diwata, by Barbara Jane Reyes (BOA Editions, Ltd., 2010). Lush, lovely, inspired. These poems are filled with startling imagery, strong women, and story, story, story. (I wrote more about Diwata in an earlier post)

Diwata, by Barbara Jane Reyes (BOA Editions, Ltd., 2010). Lush, lovely, inspired. These poems are filled with startling imagery, strong women, and story, story, story. (I wrote more about Diwata in an earlier post) The Solemn Lantern Maker, by Merlinda Bobis (Delta, 2009). This novel begins just six days before Christmas with a mute boy trawling the streets selling his handmade paper lanterns. Add to this his best friend Elvis (who holds a terrible secret), an injured and missing American tourist, and a post-9/11 let’s-freak-everybody-out media frenzy, and what do you have? A really good story.

The Solemn Lantern Maker, by Merlinda Bobis (Delta, 2009). This novel begins just six days before Christmas with a mute boy trawling the streets selling his handmade paper lanterns. Add to this his best friend Elvis (who holds a terrible secret), an injured and missing American tourist, and a post-9/11 let’s-freak-everybody-out media frenzy, and what do you have? A really good story. Growing Up Filipino II: More Stories for Young Adults, Cecilia Brainard, ed. (PALH Books, 2009). I would recommend this anthology even if I didn’t have a story in it. It’s one of those books I’d wished I’d had as a teenager and young adult, simply because it’s affirming to have our experiences transformed into a narrative on the page. You’ll find bits and pieces of yourself and yours in these stories, for sure.

Growing Up Filipino II: More Stories for Young Adults, Cecilia Brainard, ed. (PALH Books, 2009). I would recommend this anthology even if I didn’t have a story in it. It’s one of those books I’d wished I’d had as a teenager and young adult, simply because it’s affirming to have our experiences transformed into a narrative on the page. You’ll find bits and pieces of yourself and yours in these stories, for sure. I’d also like to recommend subscriptions to literary journals that seem to consistently support the work of Filipino writers. Bamboo Ridge Press, The Asian American Literary Review, and Manoa instantly come to mind.

I’d also like to recommend subscriptions to literary journals that seem to consistently support the work of Filipino writers. Bamboo Ridge Press, The Asian American Literary Review, and Manoa instantly come to mind.